The COVID-19 vaccine is perhaps the most important cargo that’s ever been shipped across the country and around the world. While getting the vaccine into the arms of individuals is the ultimate goal, getting the doses to their destinations safely and efficiently is equally important—and it’s no easy task.

The COVID-19 vaccine is perhaps the most important cargo that’s ever been shipped across the country and around the world. While getting the vaccine into the arms of individuals is the ultimate goal, getting the doses to their destinations safely and efficiently is equally important—and it’s no easy task.

A panel of experts, including alumni from Elmhurst University’s master’s program in supply chain management (MSCM), recently discussed the challenge of delivering the vaccines during the webinar, A Look Inside Operation Warp Speed and the Coronavirus Vaccine Supply Chain.

Tim Engstrom, MSCM ’03, Elmhurst University’s executive in residence and a faculty member in the Department of Business and Economics, moderated a discussion that examined a number of points in the complex process.

As a supply chain consultant, Michael Wohlwend of Alpine Supply Chain Solutions, understands how one disruption in the chain of delivery can upend the entire process. He described the complexity and sheer number of organizations and entities involved in the supply chain, starting with suppliers and ending with consumers. In the early to mid-2000s, technological advances in pharmaceutical tracking and distribution helped to lay the groundwork for the historic COVID-19 vaccine rollout, he said.

Before any vaccines are loaded onto a truck or plane, delivery methods have to be thoroughly tested. That’s the responsibility of people like Gary Hutchinson, president of biopharmaceutical cold chain engineering firm Modality Solutions. His company worked with manufacturers and members of Operation Warp Speed to map out an expected vaccine delivery network. The network then was tested in a simulation chamber for hazards like temperature, pressure, vibration, shock and relative humidity. “The combination of these hazards is what can cause harm to the vaccine,” he said.

The ultra-cold storage requirements of the Pfizer vaccine have been grabbing the headlines—and for good reason, said Ian O’Malley, MSCM ’12, director of strategic sourcing at University of Chicago Medicine. So the first thing his hospital system did was to secure ultra-cold freezers. “Every hospital in country started buying them around July-August,” O’Malley said. “That was going to be the bottleneck to distributing this vaccine.”

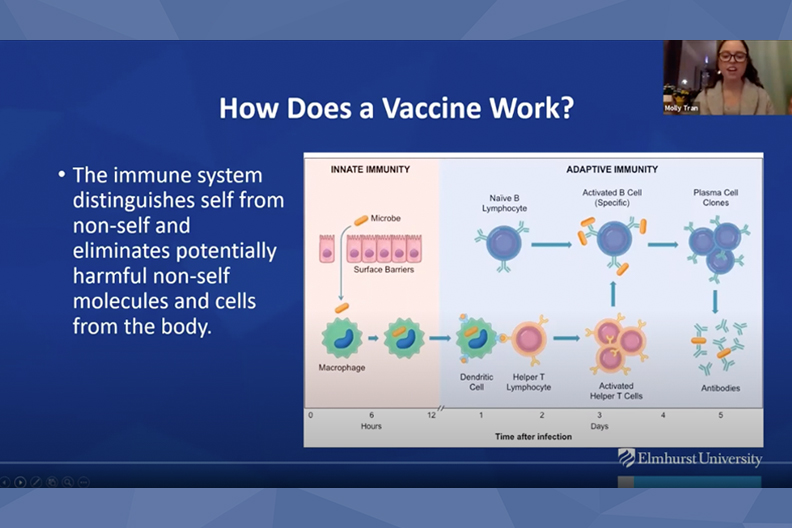

In her webinar introduction, Molly Tran, director of the Master of Public Health program, explained how the vaccines were developed and why the cold storage is important. Some of the material used to make the vaccine is very unstable, she said, “so when you’re working with it in a lab setting, keeping it at these really, really cold temperatures helps prolong its life.”

Besides the vaccines themselves, O’Malley also described shortages of syringes and personal protective equipment, which is an ongoing issue. “The supply chain has not recovered,” he said. “We are still ordering direct from China.”

The webinar was presented by Elmhurst University’s M.S. in Supply Chain Management program.